FAQ's

| ||||

Q. very old 1920? marked $ 2.50 under the name - any idea what it could sell for today? thanks for your response. A. No response. (I don't appraise tools.) |

| ||||

| ||||

|

Q.Can you include information on some of the other Disston handsaws - like the 554? A. I'm guessing the 554 is the one-man crosscut saw featured in the 1932 catalog. I chose to focus the Institute website on carpenter's and woodworker's handsaws and back saws because that was my area of experience. I've been saying for over 15 years that long saws should have a website of their own, set up by someone who knows more about them than I do, but it's never happened. I've come to know more about them by answering emails from people who ask about their crosscut saws, but I wouldn't be a very good host for a website because I own only two long saws -- a Keystone one-man saw and a two-man of unknown manufacture. They are so bulky, I wouldn't want to own a pile of them. |

|

|

Q. I am just getting into the collecting of Disston saws. My concern is what is a safe way to clean the rusted and stained saws I have. I don't want to endanger any of the original Disston logo/label on a saw, what is safe to use. Also, what is the best way to clean the Disston emblem on the handle?

A.

The important thing to do is use a sanding block if there is rust to be

removed. Holding an abrasive in your hand, whether sandpaper,

steel wool, a rag with rubbing compound, or whatever you choose,

will erode the steel unevenly and you are likely to wear away the etch.

|

A. It's a graphic, not an accurate rendering of my saw. |

|

|

Q. Why is your website so hard to read on my phone? A. It's old-school bare-bones HTML, from the days when everyone used a desktop or laptop, and I laid out pages to look like a magazine. |

|

The best question ever asked of the Institute: Q. I'm an old hardware guy, literally. I grew up in a hardware store that my father owned for nearly 25 years. He sold it in the early seventies. My earlier years with Disston goes back to [talking with salesmen], and that is a long time ago. Reason for my email is really simple. There are still a few of the old Disston sales people that have memories of more than catalogs. Hence the reason for the "wheat handle" design question. Obviously rosewood, apple, maple or even bakelite have their signatures on quality, the wheat represents teeth, pitch, which is never discussed. All these collectors really have no idea there is, or was, a meaning for that design. I know the medallion and etching in the blade is important but thought you would like to go back to work and find the key. [Edited of personal details and names.] A. Your email inspired some time of thought. Several years ago I read an online comment on a tool collectors' website, making a claim similar to yours about the symbolism of the wheat carving. It sat with me, because like your email, the author didn't elaborate or provide any printed source of his information. Despite that, I wanted to know if there is something to that claim, and if so, how deep did the symbolism go? Was it simply a folk art chip carving motif that was easy to reproduce? Disston's No. 12 saw, first sold in 1865 appears to be the first commercially-produced handsaw with a carved handle. Could it be only an embellishment to make the saw more attractive without any thought given to symbolism? Sure it could. Was the symbolism the rebuilding of cities to bring back the livelihood and strength of the restored nation at the close of the Civil War? Maybe. Was it religious symbolism with reference to the Lord's Prayer? Or maybe it's a visual comparison of saw teeth to grains of wheat on the stalk. The resemblance is remarkable, and it makes perfect sense to point it out if you are a tool salesman. The image of the rows of wheat kernels I saw when looking on Google the other night has me convinced what you wrote to me is true: wheat looks like saw teeth. I'll go one further: The wheat carving points out to us that saw teeth are as regulated and basic to man's progress in a civilization as the grains of wheat that go into our daily bread. The question now is the same one I had when I read the claim about the wheat carving several years ago. Why is there no published reference to the meaning of the carving? Disston put all sorts of references in advertising to their company's early history, their innovation, and their place in the advancement of technology. Disston even published a book in 1916 called The Saw in History, the first page of which gives examples from nature that may have inspired the first saws made by man. It lists the snout of a sawfish, the jawbones of other fish and serpents, and the tail of a wasp as candidates. No mention of wheat, which means it was not in the mind of the writer hired by Disston to assemble into a book the fifteen pages of research someone in the company had done, combined with fifty pages of saws from their then-current merchandise line. Was "wheat equals saw teeth" the intended message Disston had for the buyer in 1865, or did the craftsman who carved the first embellished Disston handle use a design he knew would be practical for mass production by a team of workers? The latter would mean the symbolism was pointed out later by a clever salesman. If it were the former, then someone in the room had the creative inspiration of a poet, because this symbolism had never been used on the handle of a saw, nor had it been used in literature. I've looked, but there's no reference to wheat and saws anywhere, and it's worthy of Shakespeare. Where did you learn the wheat carving is a symbol for saw teeth? There is nothing out there. The topic got my attention when I first read it years ago, but your email prompted me to look more, and the answer is elusive. (The reader who sent this question didn't actually ask a question, instead he suggested I go back to work and "find the key." I responded with the above reply, but he didn't write back, and I never found out where he had heard about the wheat symbolism. I assume it was from the salesmen he named in his email.) Like the nib topic, the significance of wheat carving could lead collectors to take sides. Unlike the nib, the carving actually has an aesthetic quality and improves the appearance of the saw. Its beauty is an end in itself, and the carving doesn't necessarily have a symbolic message. There's no reason, however, we can't consider the analogy between wheat kernels and saw teeth. |

A.

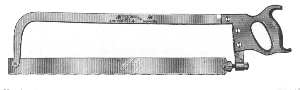

The meat saw was manufactured by Disston from the 1850's until 1955. The earliest ones are

labeled H&C Disston. Charles Disston was Henry's brother.

A.

The meat saw was manufactured by Disston from the 1850's until 1955. The earliest ones are

labeled H&C Disston. Charles Disston was Henry's brother.

Q.What do you think of this?

Q.What do you think of this?

A.

You have what is called a saw vise. It was a common tool, used to hold saws

for sharpening. The C-clamp attaches the vise to a table or bench top. The

No. 2 pivots forward and back, and the

No. 1 does that as well as swing left or right on a ball joint. Both are

about 9 or 9 1/2 inches wide.

A.

You have what is called a saw vise. It was a common tool, used to hold saws

for sharpening. The C-clamp attaches the vise to a table or bench top. The

No. 2 pivots forward and back, and the

No. 1 does that as well as swing left or right on a ball joint. Both are

about 9 or 9 1/2 inches wide.

Q. I have a Henry Disston D-8 For Beauty, Finish, and Utility, this Saw

cannot be Excelled. It's better than the one on your webpage. I can send you a

photo if interested.

Q. I have a Henry Disston D-8 For Beauty, Finish, and Utility, this Saw

cannot be Excelled. It's better than the one on your webpage. I can send you a

photo if interested.

Q. Was "Warranted Superior" a Disston brand?

Q. Was "Warranted Superior" a Disston brand?

Q.I have a Disston saw with a medallion not shown on your website. It has a pattern of circles around the keystone. When was it made?

Q.I have a Disston saw with a medallion not shown on your website. It has a pattern of circles around the keystone. When was it made?

You have an example of a Disston saw made after the family sold their corporation to HK Porter in 1955. The quality of the saws spiraled into a low state as the company tried to cut costs and the market for handsaws dried up quickly. Why aren't these saws featured on the Disstonian Institute website? Imagine the enthusiam a collector and researcher of Model A Fords would have for a 1978 Ford Fairmont.

You have an example of a Disston saw made after the family sold their corporation to HK Porter in 1955. The quality of the saws spiraled into a low state as the company tried to cut costs and the market for handsaws dried up quickly. Why aren't these saws featured on the Disstonian Institute website? Imagine the enthusiam a collector and researcher of Model A Fords would have for a 1978 Ford Fairmont.