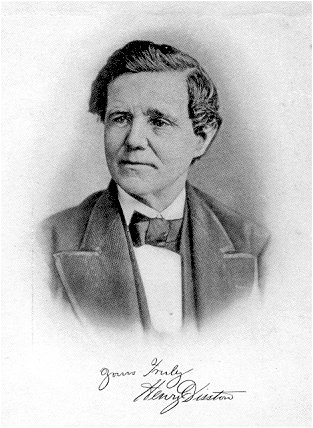

Henry Disston (1819-1878)

Pioneer Industrialist Inventor and Good Citizen

Taken from a publication based on an address

Taken from a publication based on an address given at a Newcomen Society dinner, Jan. 17, 1950.

© 1950, Jacob S. Disston, Jr.

Newcomen Publications, Princeton University Press.

My fellow members of Newcomen:

ON THIS OCCASION, the 244th Anniversary of the birth of Benjamin Franklin, I regard it as peculiarly fitting to be called upon to address you on the life of my Grandfather, Henry Disston, and upon the indisputable influence that he exerted upon American Industry, not only in his own time but in this day and age, as well.

Although born more than a century apart, there are many parallels to be found in the lives of Benjamin Franklin and Henry Disston, both of whom lived according to the best traditions of this venerable Society.

Franklin and my Grandfather both came from good English stock. Both had Philadelphia as the arena of their greatest endeavors, Franklin by his own choice, Henry Disston by the hand of fate. They both started from scratch to make their fortunes and find their places in society. And both had won wide recognition and respect while still in their twenties.

In character, too, they had much in common. Neither would admit defeat in the face of a measure of adversity that would have crushed men of lesser mettle. Both possessed those qualities of kindness, generosity, and justice that won and held the genuine affection of their associates.

Both commanded respect by their abilities. Their probing minds sought always to improve what they had, and to better the lot of their fellows, particularly those dependent upon them for the means of earning a livelihood.

Henry Disston did not set out to build an industry or to create a dynasty. He had inherited a remarkable genius for mechanics and he had served an exacting apprenticeship in his trade, an apprenticeship which combined with his heritage to make him a perfectionist in everything he attempted.

In his veins ran the same rich blood that gave courage to the hearts of his Norman ancestors who followed William the Conqueror to England and who later made worthy places for themselves in business, industry, agriculture, and the Church.

From his grandfather, William Disston, a mill owner and operator near Tewkesbury, England, Henry inherited his native business ability. From his father, Thomas Disston, a skilled Mechanical Engineer, Henry inherited his natural ability with tools and inherited that rare quality we recognize today as honesty of workmanship which is ingrained in the character of the perfectionist.

Without the courage of his forbears, whose motto, Et Decus Pretium Recti, means Both the Glory and Reward of Integrity, Henry Disston probably would have disappeared into obscurity before he was out of his teens, because almost from the day he landed in America, as a boy of 14, he was beset by misfortune and tragedy. Three days after arriving in Philadelphia he and his 16-year-old sister, Marianna, were orphaned by the sudden death of their father, Thomas Disston, who had brought them there. The firm to which Henry apprenticed himself and with which he remained during seven years was unable to pay him his wages when he left them at the age of 21, and he was forced to accept sawmaking tools and raw material in lieu of cash.

His early business career was complicated, too, by a series of disasters which he refused to take lying down, overcoming his ill fortune by sheer determination and resourcefulness, to become in later years an outstanding industrialist and humanitarian.

Henry Disston, Mr. Chairman, was born in Tewkesbury, England, on May 23, 1819, the third child of Thomas and Ann Harrod Disston. When Henry was about four years old Thomas moved his family to Derby, in Nottinghamshire, where he engaged in the manufacture of lace machines. There, Thomas invented a machine for making a certain fine, rare, and beautiful lace, and as Henry grew up he instructed the boy in his business and in the general principles of mechanics.

Since no lace of the kind produced by Thomas Disston's machine was then manufactured in the United States of America, a group of business men made him a tempting offer to bring his machine to this Country and set it up in a mill at Albany, New York. Thomas accepted the offer and, taking with him his machine, his son, Henry, and his daughter, Marianna, he sailed for America. After a tedious 60-day voyage they landed at Philadelphia, early in 1833, where as stated, Thomas died of apoplexy, three days later. The fate of Thomas' lace machine is not known, beyond the fact that it was taken from the ship and sold, the money being sent to his widow in England.

Marianna found refuge in the home of friends, and in due time was happily married. Henry, remembering his father's advice that a skilled tool maker always could earn a good living, apprenticed himself to Lindley, Johnson & Whitcraft, a firm of sawmakers in Philadelphia, where he learned to make saws and the tools required in their manufacture. When he left the firm, in 1840, his accumulated savings and the tools and raw material he had accepted for wages due him, amounted to about $350.

With that as his total capital, Henry Disston rented a tiny basement at 21 Bread Street, not far from Second and Arch (then known as Mulberry) Streets, and built his furnace with his own hands. Unable to afford a ton of coal, he borrowed a wheelbarrow and hauled the coal he needed from Delaware River docks a mile away.

At the outset of his business career, Henry Disston had a serious obstacle to surmount. English saw manufacturers held a virtual monopoly in the American market, in which there existed a strong prejudice against tools made in this Country. He knew then that he had to make better saws than any made up to that time. He also knew that he would have to break down that prejudice. That he succeeded is evidenced by the fact that the firm he established is the only American manufacturer of saws in existence at that time which has survived to this day.

Henry Disston not only built his own furnace, but also fired it himself and tempered his own saws, smithed, ground, set, and filed them. Later, he trained others to make saws to his standards.

To meet the competition, he put into his saws every measure of quality within his skill and within knowledge of the art of sawmaking, and proved to the merchants their superiority over other saws. An interesting anecdote describing his early sales technique is treasured in the Disston archives:

A plainly dressed young man entered a hardware house. He called for the proprietor and asked to see a carpenter's saw. The saw was brought, and the stranger, examining it carefully, remarked that it was good for nothing. Then, the story goes, he suddenly broke the saw with a smart blow on the counter.

"Who are you, Sir?" said the proprietor in some consternation.

"I am called Henry Disston," was the answer, "and here is a saw that I defy you or any other man to break with similar treatment."

He laid down one of his own saws. The dealer, who later headed one of the city's largest hardware establishments, said, after mentioning the incident, that the trade was forced to buy the saws of the young manufacturer because of their obvious superiority.

However, years of bitter discouragement lay ahead, before Henry Disston was to taste the pleasant fruits of his labors and of his high principles. He was forced to sell his saws at such a narrow margin of profit that at the end of three years he was no better off than he was when he launched his business.

Not long after opening his shop he married Amanda Mulvina Bickley. They had been married about a year when twins, a boy and a girl, were born to them and lived but a few hours. Henry's wife was so desperately ill that her physician, to assure her the quiet she needed, forbade Henry to complete the saws he had in process. Her death left him not only penniless, but bereft of her love and encouragement.

An old friend pressed upon him a loan of $5 with which he went back to work with a heavy heart. He would spend three days of each week soliciting orders and the next three days in making the saws, which he delivered to his customers on Saturday evenings.

On November 9, 1843, he married Mary Steelman, a direct lineal descendant of Daniel Leeds, who played a prominent role in the early development of New Jersey.

In the next year, 1844, he met a Mr. H., who induced him to move into a property he claimed to have purchased and which had the advantage of steam power. He borrowed $200 to equip the new shop, the first steam saw factory in the United States. Almost immediately misfortune struck again. Mr. H., it developed, had not bought the property, but had merely leased it. He attempted to make off in the night with his books, but was stopped by the real owner, who put the matter into the hands of the Sheriff. The latter seized Henry's possessions and sold them for back rent. Again Henry was forced to borrow money to extricate himself from his difficulties.

A new landlord then took over the premises and doubled the rent. This forced the young saw maker to move a second time. He had only occupied his factory, at Third and Arch Streets, Philadelphia, two years when he was turned out once more, He moved to a location in Maiden Street, later called Laurel Street. That shop also had steam power.

The year was 1846. The Mexican War, officially declared by the U.S. Congress on May 13, spurred the demand for saws and other tools, and the Disston business prospered. Misfortune, however, had not yet finished with the young manufacturer and, in 1849, the year gold was discovered in California, she dealt him another disastrous blow. A boiler explosion blew his shop to splinters, burned the building to the ground, and Henry escaped with his life, although not without injury.

Now thoroughly disgusted with renting, he bought a nearby lot and in two weeks had erected a shop which he owned, equipped, and had in operation. That shop, although only 20 square yards in area, was the nucleus of the great industry that today bears his name.

By 1850, Henry Disston had come a long way from the little cellar in Bread Street, Philadelphia. Most users of saws recognized the Disston trade mark as a symbol of excellence and dependability.

Henry knew that the workmanship in his saws could not be surpassed; knew that improvements in that direction were impossible. But he knew that better steel was possible, and he set out to make it; with a result that, in 1855, he poured the first crucible of saw steel made in America. He had expanded his manufactures into other product lines, so that his first catalog, issued that same year, listed a wide variety of saws, knives, trowels, squares, levels, gauges, and "springs made to order."

However, a persistent prejudice against American-made steel forced him to conceal the fact that he was making his own. It was not until the quality of American steel was established beyond question that Disston's secret was revealed.

Thus Henry Disston stands forth not only as a workman devoted to perfection in his craft, but as a man of vision, with a Scientist's consecration to the betterment of humanity's lot. He never stopped seeking better and simpler methods of manufacture, better designs, and, above all, better quality in his goods.

This facet of his code was exemplified in a statement which he repeated frequently during his lifetime:

"If you want a saw, it is best to get one with a name on it which has a reputation. A man who has made a reputation for his goods knows its value as well as its cost, and will maintain it."

When the severe financial crisis of 1857 swept the Country and brought failure to many business houses, Henry Disston was ready and he successfully weathered the storm.

In 1861, two events occurred which did much to further the success of his flourishing enterprise. The first was a tariff on foreign saws and tools, which spurred the sale of Disston products. The second was the beginning of the War Between the States.

Henry Disston loved the United States He felt that he owed much to his chosen country. He was a real patriot, and he knew that his feeling was matched by that of his employees. To those who wished to join the colors he offered to pay, during their absence, a sum equal to half of their Army pay and promised that their jobs would be waiting for them upon their return. About 25 of the men enlisted, including his eldest son, Hamilton, to whom a commission was offered. Hamilton declined it, however, preferring to share the hardships and fortunes of the men with whom he had worked in the factory.

At the same time, Henry Disston offered his manufacturing facilities to the Federal Government, knowing that large quantities of war material would be needed. His offer immediately was accepted, and he began at once the manufacture of scabbards, swords, guns, knapsack mountings, curb bits, and other items, in additions to saws, keeping the plant in operation day and night. The introduction of armored warships led to his increasing his rolling the outside cuts and a jigsaw cutting the inside holes, two men were able to increase their production to 165 dozen in a day.

Development of the bandsaw in the Disston works and by sawmill engineers eventually revolutioned the lumber industry, which formerly had depended upon the circular saw.

In the last year of the Civil War, it became increasingly difficult for the Disston Works to obtain good files. This led Henry Disston to embark upon their manufacture, in order to supply the needs of his own factory. The files he produced, like his saws, were of such superior quality that the trade soon began to clamor for them, and he was forced to put them on the market. Today, the company makes more than 250 kinds, and uses nearly a half million files in its own operations.

When Hamilton Disston returned after the war, Henry took him into partnership and the firm name was changed to Henry Disston & Son. Hamilton had worked in the shops for seven years to learn the business.

Another change was made in 1871, when Henry's second son, Albert H. Disston, who had been serving in the accounting department and showed promise of brilliance in financial matters, was taken into the firm and the name became Henry Disston & Sons. Then at three to four year intervals, the three remaining sons came into the business as partners. These were Horace C., William, and my father, Jacob S. Disston. The business was incorporated in 1886.

In 1871, Henry Disston, always mindful of the welfare of his employees, felt that they would be better off from the standpoint of health if the factory were moved away from the congested section of the city in which it then was located. He felt also that the plant facilities should be expanded. At Tacony, a few miles northeast of the city, he purchased a six-acre tract on which there was a sawmill. This mill was refitted at once, and put into operation more as an experimental and testing laboratory for Disston saws and other tools, than for its lumber production.

Gradually, other purchases increased the property at Tacony to 350 acres. All ground not reserved for factory sites was laid out in building lots, streets, parks, and other public improvements for the establishment of a town. Tacony then consisted of only 12 houses. By 1880, in addition to a new factory, the Disston Company had erected 122 homes, many of which were purchased by employees through a building and loan association established by the firm. The company also installed sewers and built a water works to serve the residents. Later, when the public school became overcrowded and the city failed to provide money for a new and larger building, the firm erected one, and turned the second floor into a library and lecture room for employees and for other residents of the community.

In connection with the breaking of ground for the first factory building at Tacony, the following story was told by William Smith, a cousin of Henry Disston and later the company's master mechanic:

"On the last Thursday in September 1872, Henry Disston, Samuel Bevan, then master mechanic, and I did the first actual work on the factory. Mr. Disston had a sawmill up here and against the advice of some friends had decided to build a saw factory on the same piece of ground. They said he was going too far away from town, but he thought differently.

"We marked out the corner that day, and Mr. Disston said, 'Now, boys, you can get started on this work at once.'

"Mr. Bevan replied, 'We'll get at it with a crew in the morning.

"'Not much,' said Mr. Disston. 'Tomorrow's Friday. I'm not a bit superstitious, but those fellows who advised us not to move up here would certainly have a good laugh if anything went wrong, and some would surely say it was because we started on Friday.'

'That's easily remedied,' said I. 'Just wait a minute?

"I ran over to the sawmill where I got a pick and two shovels and we started on the building then and there, Henry Disston wielding the pick, Sam Bevan and I starting with the shovels."

The first buildings put up were a file works and a handle factory. Both were enlarged later by the addition of large wings, the upper floors of which were used for tool making.

A little over a month after ground was broken at Tacony, fire destroyed the etching room at the Laurel Street plant and parts of the handsaw and circular saw departments, as well as the entire handle shop. A temporary handle department was set up immediately in the new file shop.

Henry Disston did not live to see the completion of the tremendous plant at Tacony. However, in 1876, he saw his products receive the highest honors at the great Centennial Exhibition In Philadelphia. In 1877, he was taken ill. For a few months he continued to give some attention to business, in spite of failing health. Then, early in 1878, he suffered a stroke. After a partial recovery he was ordered to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to recuperate. He returned home on March 9th of that year, apparently much improved in health, but on the following evening he suffered a second stroke from which he never recovered. Death came in the night of March 16th, 1878, in his 59th year.

A little over a month later on April 26th President Rutherford B. Hayes visited the Disston plant and was so impressed that he expressed a desire to return for a private tour of the establishment. During his visit a rough piece of steel was offered to him for inspection, and Hamilton Disston told him a saw would be made from it and presented to him before his departure. Forty-two minutes later, he received the finished handsaw with his name etched on the blade.

Henry Disston's only venture into politics was concerned with President Hayes, when, in 1876, he was chosen one of the Pennsylvania electors for the Hayes-Wheeler ticket.

In the brief space of 38 years, Henry Disston rose from the very bottom of the ladder to the pinnacle of success. Although the fulfillment of his plans for Tacony and for his great manufacturing plant was not for him to see, yet he found great happiness in his five sons who had taken their places in the management of the Disston enterprise while he still lived.

The importance of Henry Disston to the City he called home did not go unnoticed by Philadelphia, which then held first place among industrial cities and justly claimed the title, The Workshop of the World.

In an editorial upon the death of Henry Disston, the pubic Ledger of March 15, 1878, said, in part:

"He was one of the men whose works have made our city famous for the superiority of the products turned out from our workshops, foundries, factories and laboratories.

"Henry Disston was a born mechanic, in the comprehensive meaning of the term. He had the faculty of observing wherein a familiar tool or implement or machine was defective; the genius to devise the means to improve it, and the handicraft skill to do the manual work necessary to carry his own device into effect. He had other qualities quite as essential to the great mechanic; he was industrious, hopeful and persevering; confident that superiority of workmanship must win success; confident that he could turn out superior work, and resolute in the endeavor to make his tools the best of their kind. He had one other priceless quality; he was not above doing with his own hands any of the labor incident to his trade.

"It is among the most honorable things to the memory of Mr. Disston that he had the unwavering good will of his workmen, and that they had in him a friend as well as an employer, always devoted to their welfare; always interested in their comfort, health and happiness; always ready with a kindly word...; they knew that the prosperity of the Disston works meant good wages for them. These things ... add to the public regret for his loss.

"Henry Disston created a new American industry. He gave to the United States the greatest saw works in the world, and founded an industrial university wherein a dozen useful trades are taught. Not only did he redeem us from all dependence on foreign countries, but turned back the tide and made them accept his products, and this simply by peaceful demonstration of superior skill in manufacturing."

There are many stories about Henry Disston and his way of getting things done. One morning in the latter part of 1873 he walked briskly into his office and spoke to Albert Butterworth, who was his Superintendent for many years:

"Al," he said, "I'm not satisfied. There must be some other way to still improve the handsaw. Why, last night, I was going over the history of Egypt and Rome, and from some of the illustrations the shape of the saw blade today is about the same as then. I've been thinking about it all night. Get a piece of chalk. Now, draw a handsaw blade down there."

Al got down on the floor and drew the shape of a straightback saw blade.

"See?" said Henry, "There's more blade there than is required. It's too wide, That width isn't necessary, and it only adds to a man's labor to push and pull a wide saw. Just cut off a section of the back curve it. Ah, that's it."

The two men worked for some time, until they had finally evolved a crude drawing of what is the pride of many a carpenter today, the skewback handsaw.

Another story illustrates a point made in the Public Ledger's editorial:

After Chicago's disastrous fire which destroyed 18,000 buildings, in October 1871, every Disston employee agreed to give one day's wages for the relief of the sufferers. Henry Disston went to Chicago personally to investigate his affairs. While he stood regarding the ruins of his agents' office he was called upon by a customer with an order for four handsaws. He promised delivery the following day, but as none were available in stock, he made them himself. They were the first steel saws manufactured in Chicago.

For many years it was Henry Disston's custom to give a turkey, or its equivalent in cash, to each of his employees at Christmas. When a long business depression that began in 1873 continued through 1874, he sent a letter to each employee, in which he wrote in part:

"Thousands of deserving mechanics throughout the land have been reduced to the verge of starvation, yet it has pleased God to favor us with an amount of work which is truly wonderful, when the times are taken into consideration. It has been our constant aim and object to provide plenty of work for our hands and pay the best wages for the same; and we point with pride to the fact that during all this time the wages of our workmen have not been reduced, and take this occasion to say that no reduction shall take place so long as our goods command their present prices.

"We desire to inaugurate the New Year with all hands contented, and should any one in our employ feel dissatisfied either with his pay or from any other cause, we request him to report at the office before January 1, 1875 and, should his complaint be just, it will afford us pleasure to set him right.

"We have departed from our usual custom of presenting each of our employees with a Christmas turkey, instead of which we are engaged in supplying daily bread and nourishment to the suffering poor; feeling that all hands would rather purchase for themselves than take one cent from the needy."

Henry Disston set aside large sums every year, after he became prosperous, for charitable purposes. Among his projects was a private dispensary, where all the poor in the vicinity could obtain medicine without charge. And during at least one severe business depression when unemployment was rife, he maintained a soup kitchen to feed the hungry and jobless.

Manufacturers who took advantage of every new circumstance to increase the prices of their goods found no favor in Henry Disston's eyes. He believed such practices to be unsound economics. Steadfastly he maintained his own price levels unless he was literally forced to increase them to stay in business, although he lowered them whenever reductions in production costs permitted. The popularity of Disston saws would have made it easy for him to increase prices many times, when he refused to do so.

An instance of his adherence to that principle occurred in 1872, when the firm issued an appeal to its "more than liberal customers" to curtail their orders as much as possible. Because, the appeal stated: "while we have increased our facilities for production about one-fifth over last year, if crowded too much we shall be compelled, in self-defense, to advance the price, and this we are trying to avoid. We do not wish to take advantage of circumstances, nor will we unless forced, for we know that all fluctuations naturally tend to give our customers trouble, and our hardware men have sufficient of that."

Even in the face of advancing costs of raw material at various times, that principle of the Founder has been adhered to as closely as possible by those he left behind to carry on the business. Often the wisdom of such a policy was proven by a sudden return of normal price levels.

We have spoken before of the Founder's attitude toward quality of product. From the very beginning of his business career he thought less of profits than of the superiority of his saws.

A hardware merchant who had been one of his early customers once told of an occasion when Henry Disston came into his store to deliver some saws. Taking one from its handle he found the blade was too soft. Henry then asked a boy to help load the saws back into his wagon. The merchant remarked that perhaps some of the saws were all right. But the young sawmaker disagreed. All had been tempered at the same time, he said, and he could not run such a risk.

Considering how badly he needed cash at that time, the incident lends emphasis to the extreme care he gave to his reputation.

The strong ties that bound Henry Disston and Es men in a relationship far deeper than that usually found between employer and employees were knit from their common interest in their craft. In Henry Disston the men recognized a master craftsman, familiar with all of their various skills, as well as a sincere friend. That bond is attested by the employment records of many men then on the Disston payroll:

When the first Disston history was compiled, in 1920, the rolls showed 21 men in continuous service for 50 years or more; 90 from 40 to 50 years; 238 from 30 to 40 years; 320 from 20 to 30 years; 763 from 10 to 20 years, and, working beside them, 2,170 younger saw and tool makers, steadily gaining in skill and experience. Many of the younger men were sons or grandsons of the older employees.

Today's employee records are comparable to those of 30 years ago in that respect, largely because the management is still in the hands of the family of Henry Disston -- his grandsons and collateral descendants -- who have been brought up in the business according to the principles laid down by the Founder. Members of the fourth generation are serving their apprenticeships to prepare themselves for greater responsibilities later on.

Excepting mention of his two marriages, I have made no reference to Henry Disston's personal life, without which this delineation would be incomplete. So far, I have kept rather closely to the story of his saw business, which to a large extent was the life of Henry Disston. Yet he had a side which was seen only by those most intimately associated with him and which, more or less directly, had an important bearing upon his career:

Henry Disston was a man of deep religious convictions and an abiding Faith, which was evident in his relationships with his employees, as it was indeed in all his relationships. He quickly was moved to compassion by any sign of suffering; and his purse was always open to those in need. Although a member of the Presbyterian Church, his sympathies extended to all struggling Christian organizations, many of which received generous gifts from him. This phase of his activities was shared by his wife, Mary Steelman Disston. A number of churches in Tacony stand on ground given by her, and many church bells in that section peal out in her memory as they call worshippers to their altars every Sabbath day. She, too, gave regularly and liberally to a number of charitable organizations, while a stream of charity perpetually flowed from her heart and hands into the more private circles of kindred and friends.

There is another place where the name of Henry Disston has a special meaning. This story again is evidence of his vision and of his desire to make the World a happier place for his fellow men. It concerns Atlantic City, New Jersey, which owes its existence largely to my Grandfather's putting into immediate action any plan he believed in and backing it with his means and with his driving energy.

About the Year 1870, according to one historian, he recognized in that section of the New Jersey Coast its possibilities as a summer resort. He at once demonstrated his faith in the idea by investing heavily in land. Some cottages and boarding houses were being built, but there was no convenient lumber supply, which made building both difficult and expensive. To remedy that situation, Henry Disston erected a large sawmill in 1872, which spurred the building of homes, hotels, and business houses and started Atlantic City on its way to becoming one of America's most popular playgrounds. He built for himself a large home which was for many years one of the show places of the Jersey shore, and which did much to maintain the character of the vicinity.

As the development of railroads led to the opening of new territory and contributed to the building of this Country, so also have large manufacturers encouraged the building of hamlets, towns, and cities by supplying the necessary materials and by drawing workers and their families to new centers of activity. Without the imagination and the courage of such men as Henry Disston to embark on new enterprises, the growth and progress of the United States would have been slow indeed.

All industries are more or less interdependent. From a score or so of basic industries, hundreds of lesser ones receive their nourishment. The lumber industry and the many industries that stem from it owe their greatest advance in large measure to Henry Disston's inventive genius and to his development of better saws, tools, and methods of manufacture. To the lumber jack in the World's timberlands, to the reapers on far flung sugar plantations, to stone masons and carpenters and workmen in a hundred trades, The name of Henry Disston means the finest tools that can be had.

Henry Disston no longer walks among the workmen in his plant, but his spirit still marches through the vast works at Tacony, and his influence is still felt in industries throughout the World.

In conclusion, Mr. Chairman, I will quote from the annual report of the Secretary of Internal Affairs of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, published in 1887:

"Mr. Disston was not a literary man. He neither wrote books nor pamphlets, nor sought the newspaper reporter. But he was a thinker, an actor, and, more than all a good man, and he had incarnated at Tacony the proofs of his good thoughts and works. Let the despairing go there if they wish to revive their hope concerning the future. . . Study the history of Mr. Disston's enterprise and the vision of a happier time will appear to you"

America still can learn lessons from the kind of man Henry Disston consistently was. Integrity of character is the greatest asset of a man or of a business!

THE END

"Actorism Memores simd aff ectamus Agenda!"